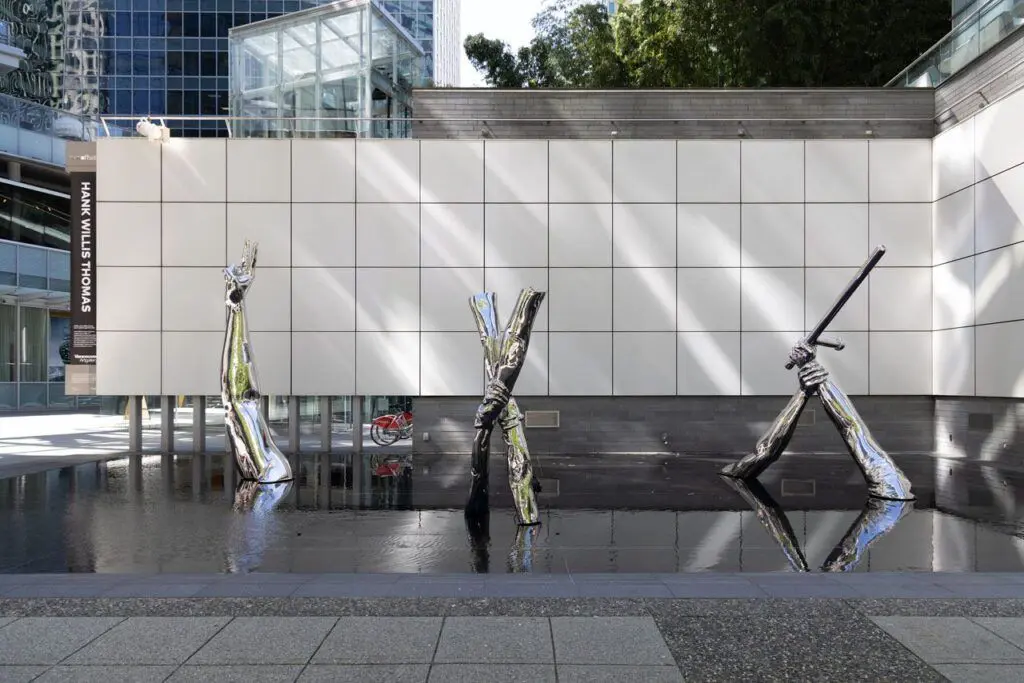

Installation view of Offsite: Hank Willis Thomas, site-specific installation at Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite from June 7, 2024 to June 8, 2025, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery

Hank Willis Thomas with his work at Offsite, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery

ABOUT THE ARTIST

In his wide-ranging conceptual art practice, Hank Willis Thomas explores how contemporary society commodifies race and gender. His works—which span photography, sculpture, installation and more—often reflect on mass media representations and social justice. Originally trained as a photographer, he is interested in how popular imagery from advertisements, mass media and visual media inform cultural attitudes. In using images featuring Black men that circulate widely in popular culture (from Nike ads to political campaign images), the artist encourages the viewer to question commercial representations and cultural stereotypes.

Thomas has increasingly made work for the public realm, creating large-scale outdoor sculptures and monuments. His public sculptures often feature an isolated gesture from a photograph or circulated image, bringing a sense of intimacy to the public sphere. For the first time, three of Thomas’ polished stainless steel sculptures are exhibited together at Offsite, the Vancouver Art Gallery’s public art program. Situated on a bustling intersection in downtown Vancouver, Thomas’ sculptures feature disembodied hand gestures that evoke gestures of protest, care and exaltation.

Thomas’ collaborative projects include Question Bridge: Black Males, In Search Of The Truth (The Truth Booth) and For Freedoms, which was awarded the 2017 ICP Infinity Award for New Media and Online Platform. In 2012, Question Bridge: Black Males debuted at the Sundance Film Festival and was selected for the New Media Grant from the Tribeca Film Institute. Thomas is also the recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship (2018), AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize (2017), Soros Equality Fellowship (2017) and is a former member of the New York City Public Design Commission.

Thomas’ work has been exhibited throughout the United States and abroad, including at the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, Pennsylvania (2008); Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland (2009); International Center of Photography, New York (2013); California African American Museum, Los Angeles (2016); and SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia (2017). His work has been included in important group exhibitions at the International Center of Photography, New York (2013); Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain (2015); Brooklyn Museum, New York (2016); and the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town (2016), among others. His work is held in numerous public collections worldwide, including the Kadist Art Foundation, Paris; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California; Smart Museum of Art, Chicago; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Thomas earned a BFA from New York University, New York, in 1998 and an MA/MFA from the California College of the Arts, San Francisco, in 2004. He received honorary doctorates from the Maryland Institute of Art, Baltimore, Maryland, and the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts, Portland, Maine, in 2017. The artist lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Offsite: Hank Willis Thomas is organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery on behalf of the City of Vancouver Public Art Program and curated by Eva Respini, Deputy Director & Director of Curatorial Programs, with Julie Martin, Curatorial Assistant. It was presented from June 7, 2024 to June 8, 2025.

Offsite is the Vancouver Art Gallery’s outdoor public art space in the heart of the city. Presenting an innovative program of temporary projects, it is a site for local and international contemporary artists to exhibit works related to the surrounding urban context. Featured artists consider the site-specific potential of art within the public realm and respond to the changing social and cultural conditions of our contemporary world.

Since the launch of Offsite in 2009, the Vancouver Art Gallery has presented twenty-six public artworks in the forms of sculpture, multimedia, film, ceramic and photo-based installations.

CURATOR: Eva Respini

PROJECT MANAGER: Julie Martin, Curatorial Assistant, Vancouver Art Gallery

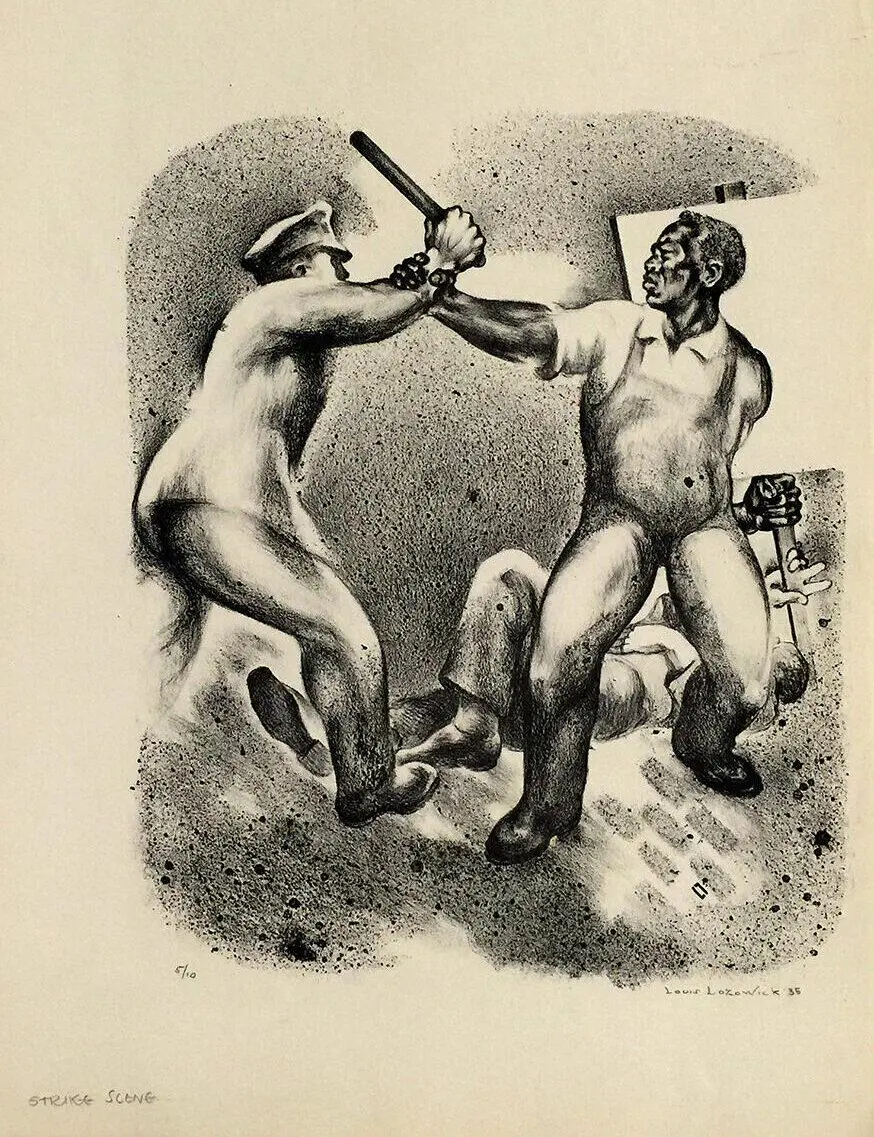

ARTWORKS: Hank Willis Thomas, Duality (Reflection), 2022, polished stainless steel, Courtesy of the Artist and Ben Brown Fine Arts; Nexus, 2022, polished stainless steel, Courtesy of the Artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; and Strike, 2021, polished stainless steel, Courtesy of the Artist and Pace Gallery; Louis Lozowick, Strike Scene, 1935, lithograph, © Louis Lozowick, Courtesy of the Estate of the Artist and Mary Ryan Gallery, New York

PHOTOGRAPHY: Jessica Jacobson and Kyla Bailey, Vancouver Art Gallery

© 2024 Vancouver Art Gallery

Offsite is organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery on behalf of the City of Vancouver Public Art Program. The Gallery recognizes Ian Gillespie, President, Westbank; Ben Yeung, President, Peterson Investment Group; and the residents of the Shangri-La for their support of this space.