A Closer Look at the Work of Firelei Báez

Delve deeper into Firelei Báez’s practice with a closer look at a selection of artworks currently on view in the Dominican American artist’s first major retrospective in North America.

Discover these works at the Gallery now in Firelei Báez, only on view until March 16, 2025.

1. Truth was the bridge (or an emancipatory healing), 2024

Firelei Báez, Truth was the bridge (or an emancipatory healing), 2024, digital prints on vinyl mesh, Courtesy of the Artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York

Truth was the bridge (or an emancipatory healing) opens the exhibition on a monumental scale, extending the length of the Gallery’s Georgia Street facade and showcasing Firelei Báez’s quintessential practice of transforming colonial maps, charts and architectural renderings by overlaying scenes inspired by mythologies and imaginative realms.

First conceived as a site-specific mural at the ICA/Boston in 2024, this banner features a 1776 map of North America’s east coast from Nova Scotia to New York City. A ciguapa—a recurring figure in Báez’s work—crouches over the map on the left panel.

The ciguapa is a Dominican folkloric creature, a woman-plant-animal hybrid, who is known to be a powerful trickster. Báez’s work is often concerned with the colonial histories of the Americas, and Truth was the bridge (or an emancipatory healing) is a compelling reminder that those histories can be reimagined for future generations.

Ultimately, Báez’s process of intervention is not one of obliteration, but rather one of recalibration.

2. (once we have torn shit down, we will inevitably see more and see differently and feel a new sense of wanting and being and becoming), 2014

Installation view of Firelei Báez, (once we have torn shit down, we will inevitably see more and see differently and feel a new sense of wanting and being and becoming), 2014, in Firelei Báez, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery from November 3, 2024 to March 16, 2025, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery

Firelei Báez considers all of her work, even sculpture and immersive installation, to be painterly due to its illusionistic qualities.

This architectural sculpture was adapted from the Sans-Souci Palace in Milot, Haiti. The palace was built between 1810 and 1813 for the revolutionary leader and self-proclaimed king of Haiti, Henri Christophe. The Haitian Revolution, led by self-liberated enslaved people against the French colonial government, was an early precursor to the abolition movements of the United States. Once a space of militant splendor, the castle has remained a ruin since the destructive Haitian earthquake of 1842.

The patterning of the sculpture’s surface is largely drawn from West African indigo printing, appropriated from enslaved peoples in the seventeenth-century American South. Indigo was a driving force in the early United States economy. This material became intrinsically woven into early American decorative and utilitarian textiles—a symbol of true-blue Americana. Báez’s intricately painted architectural surfaces include symbols of healing and resistance.

Expanding the painterly surface into an architectural dimension, Báez invites visitors to walk through and touch the archaeological ruin.

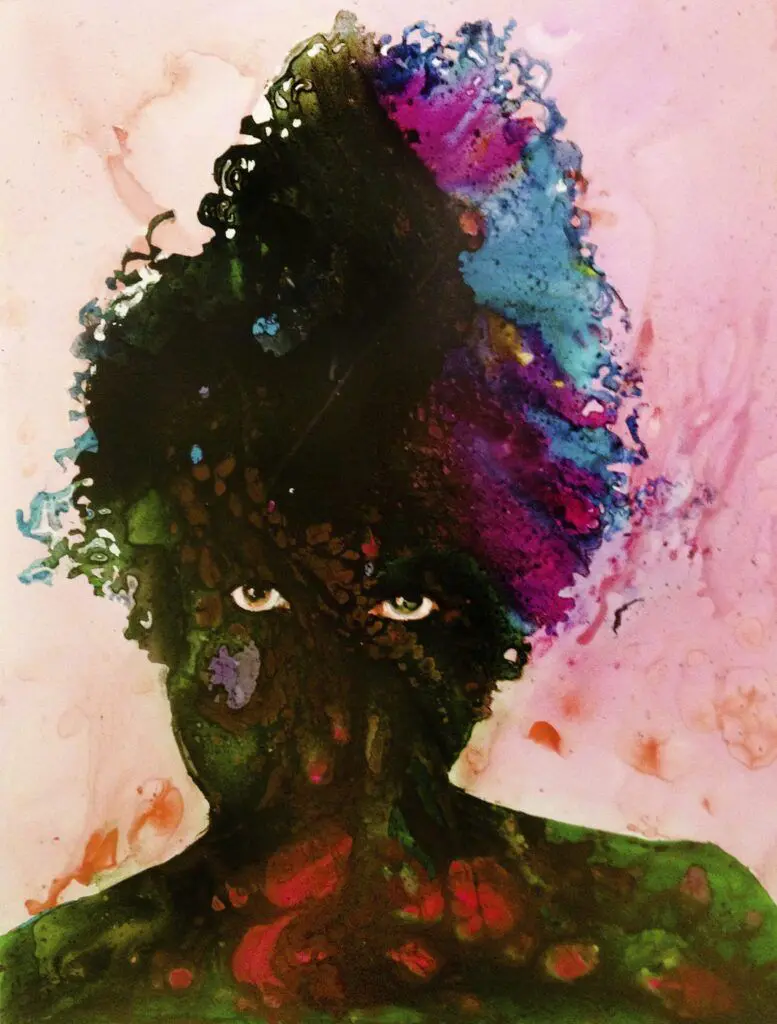

3. Fire wood pretending to be fire, February 12, 2012, 2013

Firelei Báez, Fire wood pretending to be fire, February 12, 2012, 2013, acrylic and gouache on Yupo paper, Collection of Carol Sutton Lewis and William M. Lewis, Jr., Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York, Photo: Adam Reich, © Firelei Báez

Since 2008, Báez has experimented with pouring paint on Yupo paper, which has a synthetic, nonabsorbent surface. Acrylic paint, gouache and ink mix and pool together, creating fluid and unfixed forms that are the basis for the artist’s figures—sometimes self-portraits, like the image you see here.

Some of Báez’s Yupo works form figures with piercing eyes, whose gaze follows us as we move. Báez describes her pouring process: “There’s the tilt of the floor, the humidity level, what I could physically reach. There are very specific limitations that become like archaeological time capsules.”

Báez also uses the technique of pouring paint to create marbled pools of colour in her later, larger canvases.

4. Adjusting the Moon (The right to non-imperative clarities): Waxing, 2019–20

Firelei Báez, Adjusting the Moon (The right to non-imperative clarities): Waxing, 2019–20, oil and acrylic on panel, Private Collection, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York, Photo: Christopher Burke Studios, © Firelei Báez

Arched portals are a recurring theme in Báez’s work—and are even echoed in the exhibition design through the doorways.

Adjusting the Moon (The right to non-imperative clarities): Waxing and Waning are imagined as portals into another world. Cosmic figures stand on the edge, slightly outside a “framed” architectural niche, with paint distorting their heads and torsos.

Limiting visibility has long been a tool for Black people and other people of colour to control their image and navigate space with greater autonomy. This form of control is dubbed “opacity” and was formally theorized by Martinican philosopher Édouard Glissant (1928–2011). “I think of opacity as, not necessarily armour, but as an assurance of a fuller self—that you can traverse the world without having to constantly pick up your entrails,” says Báez.

While many of her subjects meet our gaze, the figures here are obliterated by a burst of colour, allowing them a right to opacity.

5. Man Without a Country (aka anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River), 2014–15

Firelei Báez, Man Without a Country (aka anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River), 2014–15, gouache, ink and chine-collé on 225 deaccessioned book pages, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, Gift of Fotene Demoulas and Tom Coté, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York, Photo: Oriol Tarridas, © Firelei Báez

This monumental work is composed of 225 individual book pages sourced from decommissioned architecture, art and engineering books, many from the Cooper Union Library in New York.

Each page is a rumination on the history of Hispaniola—the Caribbean Island divided between the Dominican Republic and Haiti—in a global context. The artist uses the pages, many of them dog-eared and gently worn, as supports for her drawings depicting fantastic figures and decorative embellishments. The work’s title references the ongoing plight of many Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent living in the Dominican Republic, where citizenship and its rights are not guaranteed.

The artist’s markings intervene across text, fusing folkloric motifs with academic writing to offer new ways of reading history and culture. Báez installs each page individually to form this wall-sized installation, suggestive of island geographies and bodies of water, which viewers navigate according to their own trajectories, resisting singular narratives in favour of multiple readings.

Firelei Báez, Man Without a Country (aka anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River), 2014–15(detail), gouache, ink and chine-collé on 225 deaccessioned book pages, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, Gift of Fotene Demoulas and Tom Coté, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York, Photo: Oriol Tarridas, © Firelei Báez

5. A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways), 2019

Installation view of A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways), 2019, in Firelei Báez, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery from November 3, 2024 to March 16, 2025, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery

A Drexcyen Chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways) is an immersive installation that invites audiences to reexamine historical narratives.

Báez creates a grotto-like space using perforated blue tarp, a material often used for shelter and refuge following natural disasters, particularly in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, where the artist’s family is from. Here, the tarps are reimagined as the night sky, or perhaps an underwater world. Tropical plants adorn altars in the space where two paintings of female figures—the exiled Haitian Queen Marie-Louise Coidavid (1778–1851) and her daughters—watch over the scene.

Installation view of A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways), 2019, in Firelei Báez, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery from November 3, 2024 to March 16, 2025, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery

The work’s title refers to Drexciya, a Detroit electronic music duo who, since 1992, have developed a speculative narrative around the mythical Drexciyans and their origin, which traces back to the Middle Passage. During the horrific transatlantic journey, pregnant African women were often thrown from slaveholder’s ships and left to drown. Drexciyan myths tell of the newborn Drexciyans, who swam from their mothers’ wombs, began to breathe seawater, and established their underwater community.

“To psychologically inhabit a femme space is a transformative gesture,” says Báez. “It is a radical positioning that could truly enable a different way of organizing space and bodies and nature and spirits—an otherwise world order.”

For further reading, an alcove nearby features a selection of books that the artist chose to accompany the installation.