A Brief History of Zines

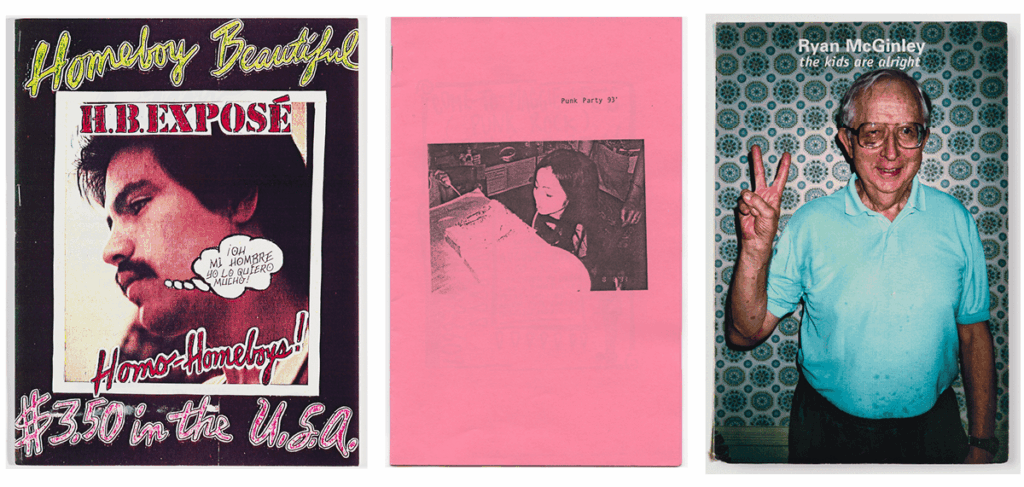

From left to right: Joey Terrill, Homeboy Beautiful, no. 1, 1978, photocopy zine, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, © and Courtesy Joey Terrill and Ortuzar Projects, New York; Maggie Lee, Party ’93, 2020, photocopy zine, saddle stitched, Courtesy the Artist; Ryan McGinley, the kids are alright, 1999, photocopy zine, saddle stitched, Collection Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons, Photo: David Vu

Since the 1970s, zines have given a voice and visibility to many operating outside of mainstream culture. Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines focuses on publications that were conceived as or called zines at the time of their making, either by their creators or by their contemporary readers.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ZINES

1969–1980: Correspondence Art

In the wake of the liberation struggles and countercultural movements of the 1960s, mail art networks emerged as a way of community building and world making outside of traditional institutions. Correspondence zines drew heavily from celebrity fan culture and appropriated mass-media images. Under pseudonyms such as Anna Banana, Count Fanzini and Les Petites Bon-Bons, numerous artists in this period took on personas that they performed as art in their daily lives and made the subject of their zines.

1975–1990: The Punk Explosion

Artists played a key role in adopting and disseminating punk’s signature publication format and do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos during the 1970s and ‘80s. Many artists’ zines in this period channeled the tropes of violence and abjection that were popularly associated with punk. Forging further links to the punk community, many of the artists were connected to bands, with their zines serving as both promotional and mythmaking tools.

1987–2000: Queer & Feminist Undergrounds

The late 1980s and early 1990s experienced what zine maker Larry-Bob Roberts dubbed the “queer zine explosion.” 1987 saw the publication of Fertile La Toyah Jackson Magazine in Los Angeles and My Comrade in New York, with Homocore appearing in San Francisco a year later. The movement that became known as Riot Grrrl also emerged by 1990. Feminist punk zines often drew on and overlapped with the queercore movement pioneered in Toronto’s zine, music and underground film cultures in the mid-1980s.

1990–2010: Subcultural Topologies

Zines by artists have consistently drawn on and contributed to marginalized and subcultural practices, such as punk. By the mid-1990s, as zines were becoming integrated into commercial art galleries, artist-run spaces and museums across North America, the lines between inside and outside, or centre and margins, became fluid.

2000–2020: Critical Promiscuity

After the year 2000, many artists who had participated as young adults in queer and feminist communities during the 1990s incorporated zine making into their studio practice, particularly in New York. These creators sought to bring the zine’s accessible format and ethos of community formation and world-making into the art world. In addition to producing print publications, zine makers organized open calls for contributions and also staged exhibitions, performances and other events to bring people together. To enhance and expand local zine scenes, fairs dedicated to artists’ publications and international travelling exhibitions-on-wheels brought zines, as well as workshops and artists’ talks, to larger audiences and to areas far beyond metropolitan art centres.

Visit the Gallery to discover the impact zines have had on popular culture and artistic practice over the last half century before the exhibition closes September 22!